Resources

Get school research and design resources and a free professional learning center built for educators reshaping what school can be.

What does LTW look like at its best?

What does Learning To Work look like at its best? Findings from Transfer Schools and YABCs New York City Public Schools' Learning to Work (LTW) program is a powerful support to youth for whom the traditional school system hasn’t worked. LTW partners...

Eskolta Fellows: Impact and Community since 2015

Since 2015, the Eskolta School Improvement Fellows Program has supported and trained 101 fellows in four key areas: leadership, community, critical conversations about equity and race, and designing change in schools. The work of the Fellows Program mirrors the...

A New Approach to Inquiry: Students As Co-researchers

“Our education system is not perfect. It’s a work in progress, and I appreciate Eskolta for acknowledging that and our schools for acknowledging that and making it better, and taking the time, because this work is not easy.”Landmark High School alum Titilayo Aluko...

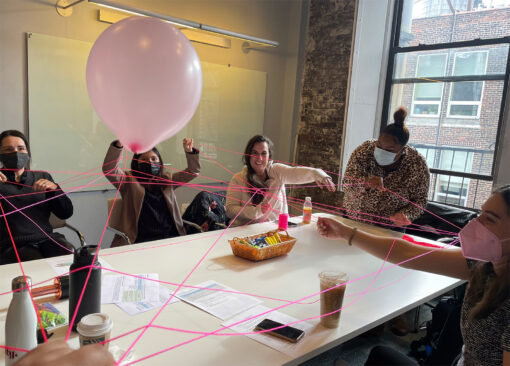

Strengthening Team Dynamics with CS4All

As demand for a technologically skilled workforce continues to increase, the ‘digital divide’ disproportionately affecting Black, Latinx, and female students who lack access to quality computer science tools and instruction remains a challenge. The Computer Science...

Dismantling Traditional Educational Molds: Lessons from Alternative Schools

"It wasn’t until high school, after changing high schools three times, that I ended up at City-As-School, a transfer or alternative school in New York City. City-As-School’s welcoming environment allowed me to have a place to heal. I was finally met with supportive...

How They Thrive: A Conversation On The Impact of Transfer Schools

On May 9th, Eskolta held an online presentation and panel discussion on our mixed-methods study How They Thrive: Lessons from New York City Alternative School Alumni. With over 100 attendees from high schools, districts, universities, nonprofits, and...

How They Thrive: Lessons from New York City Alternative School Alumni

“[My transfer school] was, I’m going to say humanizing... being seen, like, literally seen, and just appreciated, and understood, and valued, and all of these other amazing things.... You get to be a human. You get to be hungry, you get to be confused. You get to...

Student-Led Action Research

“[This project] helped me with my growing, my team-leadership skills. It has definitely opened me up with feeling confident about making changes at my school.”When City-As-School student Nicholas Cannon was first searching for a summer internship in 2020, he wanted...

Studying Resilience

Studying Resilience: A Collection of Classroom Activities to Explore the History, Reality and Potential of Youth in Alternative High Schools is curriculum guide developed through a collaboration between Eskolta and transfer school educators from Voyages Preparatory...

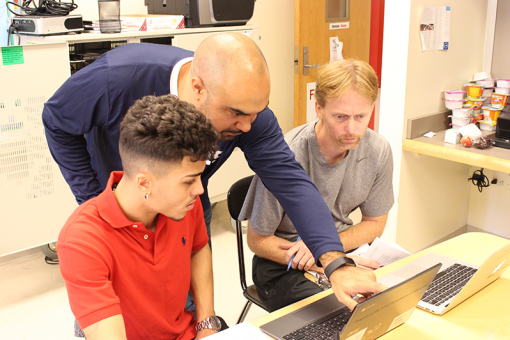

Empowering Teacher Teams to Improve Instructional Practices

“I’ve developed strategies that have been total game changers for me and had a huge impact on student learning. Things that I just would not have come up with on my own without the support of my lesson study team.” Empowering Teacher Teams to Improve Instructional...

Let Difference Thrive—and Drive Innovation

Let’s work together to build better. Complete this form to start the conversation.