This conversation was an inspiring jumping-off point for our partners in the transfer school community to come together and push for changes so that these schools will not continue to be penalized by the system. Currently, one in five New York City transfer schools are designated as Comprehensive School Improvement schools, a designation for low-performing schools that requires them to implement a change plan to reach certain benchmarks while essential programs like Learning to Work have undergone a 25% cut, resulting in cuts to staff as well as paid internships for students.

Evin Orfila, a school aide at Liberation Diploma Plus High School, the transfer school he graduated from, co-moderated the panel with Michelle Fine, Distinguished Professor of Critical Psychology, Women’s Studies, American Studies and Urban Education at CUNY’s Graduate Center.

Alternative transfer schools: filling a critical gap in our education system

More than 100 attendees heard first from Evin about his own experience at Liberation and the deep appreciation he felt for his teacher and principal there, who demonstrated compassion and support as he faced multiple overlapping challenges and whose support continued even after he completed high school and went on to graduate with honors from college. “I needed a home. Liberation was that. I needed to see somebody like me being successful, somebody who could walk on water, brave enough to challenge the powers that be, but gentle enough to nurture me when I fail.”

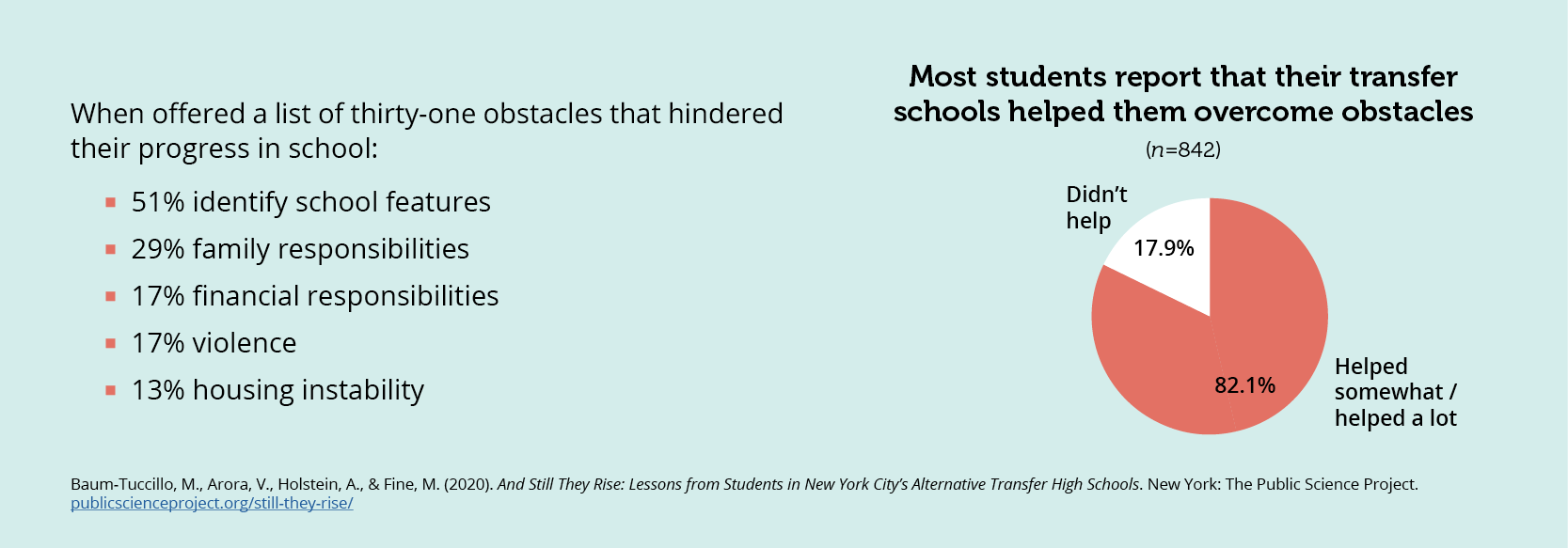

His and Joshua’s stories illustrated broader themes that researchers Varnica Arora, Mica Baum-Tucillo, Ali Holstein, and Michelle Fine encountered in their research. And Still They Rise is a secondary analysis of 842 survey responses from alternative transfer high school students about their educational experiences, collected as part of the Transfer School Discovery Project facilitated by Eskolta in 2018. Mica, a social worker and herself a transfer school alumna, presented the report findings, highlighting four non-negotiable elements of transfer schools:

- Opportunities and resources aligned with student needs

- School cultures of care and compassion

- High expectations attuned to students’ needs and supports

- Ecologies of personal and collective responsibility

Across NYC, the students transfer schools serve are more likely to be Black and Latinx, to experience high economic need and housing instability, to be English Language Learners, and to be classified as in need of special education. As Mica noted, the unique approaches and supports transfer schools provide are part of tempering systemic inequalities for these students: “We find that transfer schools provide opportunities and resources that mitigate the effects of racialized austerity, neighborhood divestment, gentrification, over-policing, and failing social safety nets. Of course, we don’t want to suggest that schools should be where we go to figure out how to fix all of these problems, but we are suggesting that in transfer schools we are finding tremendous counters to these issues.”

Thank you to our moderators, presenters, and panelists

- Michelle Fine, Distinguished Professor of Critical Psychology, Women’s Studies, American Studies and Urban Education at the Graduate Center, CUNY

- Evin Orfila, School Aide, NYC Department of Education; Alumnus, Liberation Diploma Plus High School

Presenter:

- Mica Baum-Tuccillo, LMSW, Research Associate, Public Science Project, Graduate Center, CUNY

Panelists:

- Joshua Applewhite, Student, Liberation Diploma Plus High School

- Nekisha Smith, Program Director, Good Shepherd Services at South Brooklyn Community High School

- LaToya Kittrell, Principal of South Brooklyn Community High School

- Tim Lisante, Executive Superintendent, District 79, NYC Department of Education

- Susie Miller Carello, Executive Director, Charter Schools Institute, SUNY

How do we ensure transfer schools are being accurately measured?

A key recommendation the report authors arrived at through a participatory process with educators, students, alumni, and community partners, is the need to develop a transparent, ethical framework for alternative high school accountability that includes various pathways to graduation, using multiple indicators and outcomes. One clear example of the need for change is the current use of the 67% graduation rate, which is a problematic and arbitrary cutoff that does not align with the goals and mission of alternative transfer schools.

Panelist Tim Lisante, Executive Superintendent for New York City’s transfer schools, District 79, and Adult and Continuing Education, and a veteran alternative school educator in NYC, was optimistic: “One of the big goals this year for Superintendent Rotundo and his team is developing attributes for a proposed accountability system for high schools…. And it’s not about no accountability. It’s about customized accountability, multiple measures, as the report says, of evidence of growth and progress. And it’s got to be transparent, easy enough to explain to families.”

In 2021, we are excited to continue advocating alongside educators, CBO partners, students, and alumni to develop an accurate and ethical framework for alternative schools that will strengthen and sustain the invaluable work they do.

Want to get involved in pushing for better metrics for alternative schools? Reach out to Savanna Honerkamp-Smith shonerkampsmith@eskolta.org